There’s nothing quite like the sinking feeling you get when you jack up your project car and discover that your floor has more holes than a block of Swiss cheese. That’s exactly what happened to me with my 1981 BMW 3-series, a car I’d been nursing back to health one weekend at a time. What started as a simple cleaning turned into a crash course in metalwork that would fundamentally change how I approached automotive projects and taught me that almost anything is fixable, if you have the skill and vision.

The Rust Revelation

My 1981 BMW 3-series had been a long-term project car on the cusp of becoming a Sunday driver, a car that had seen better decades but I was determined to restore that unmistakable E21 charm. The exterior had always looked decent enough, a lot of patina with a few surface rust spots here and there, but nothing that screamed “structural disaster.” It wasn’t until I decided to tackle some much deserved carpet cleaning work that I discovered the true extent of the rot lurking beneath. I started with a carpet spot cleaner to spruce it up a bit, but when the cleaning head hit the floor, all I heard was a distinct crunching sound. I peeled back the carpet to find the floor was worse than I could have imagined.

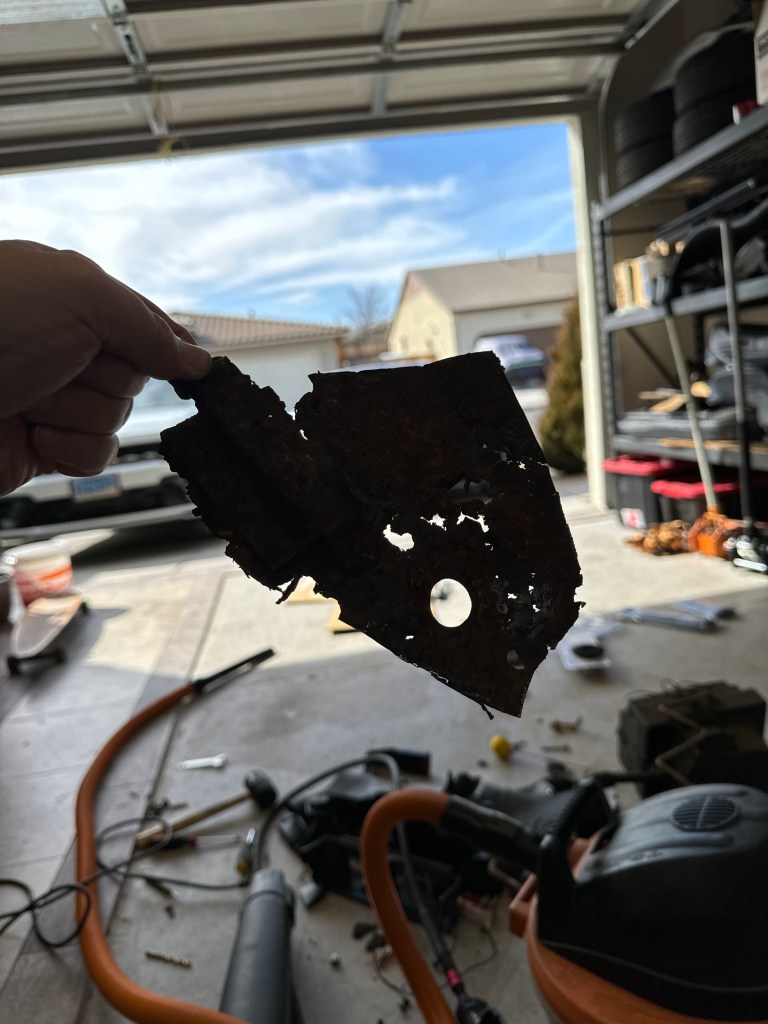

The first hole I found was behind the driver’s seat, about the size of a golf ball. “Not too bad,” I thought, already mentally calculating the cost of a small patch panel. Then I found a pin hole, then another, then another. By the time I’d finished my inspection, I’d catalogued enough holes to make the car look like it had been used for target practice.

The worst part was that the rust was trailing from the opposite corner from the pedal box in the inner sill. Turns out this is a major rust area for E21s. Mine was a pretty bad case with the rust eating through the front sill and the entire jacking pad. Knowing the majority of the extent of the rust, I had a to decide how to proceed. The smart move would have been to walk away. Find another E21 with a solid floor and transfer all my good parts over. But this car had been with me for 8 years already. I had learned so much with this car already. I couldn’t just let it go. We had history. Besides, I’d always been curious about welding, and this seemed like the perfect excuse to finally learn. So I did what any reasonable car enthusiast would do: I bought a MIG welder from Harbour Freight and dove headfirst into the world of molten metal.

Surgery on the Floor Pan

Before I could start throwing sparks around my garage, I needed to learn the basics. Luckily, my neighbor Cassidy had some experience and was willing to teach me the basics. With Cassidy at the helm, I learned the fundamentals: proper gun angle, travel speed, and the subtle art of reading the puddle. My first attempts looked like someone had sneezed molten metal across the steel, but gradually, with Cassidy’s patient guidance, I started to get the hang of it.

The key breakthrough came once I learned to listen to the weld. A good MIG weld has a distinctive crackling sound, like bacon frying in a pan. Too much wire speed and it sounds angry and spattery. Too little and it becomes a stuttering mess. Once I learned to trust my ears as much as my eyes, everything clicked into place. This skill is the most important in my mind, as not all metal is the same, and your settings can change as various factors are involved. Being able to adjust based on the sound is how you become a great welder. But it takes lots of practice with doing it wrong before you know how to do it right. I had a long uphill battle ahead of me.

With a few practice sessions under my belt, it was time to tackle the real work. The first step was cutting out all the bad metal, a process that was both therapeutic and heartbreaking. There’s something oddly satisfying about cutting away rust, watching decades of decay fall away in chunks, but it’s also sobering to realize just how much of your car has been slowly disappearing. The first incision was the worst, but once it’s done, there is no going back. I felt less scared to dive in once the major cuts were made.

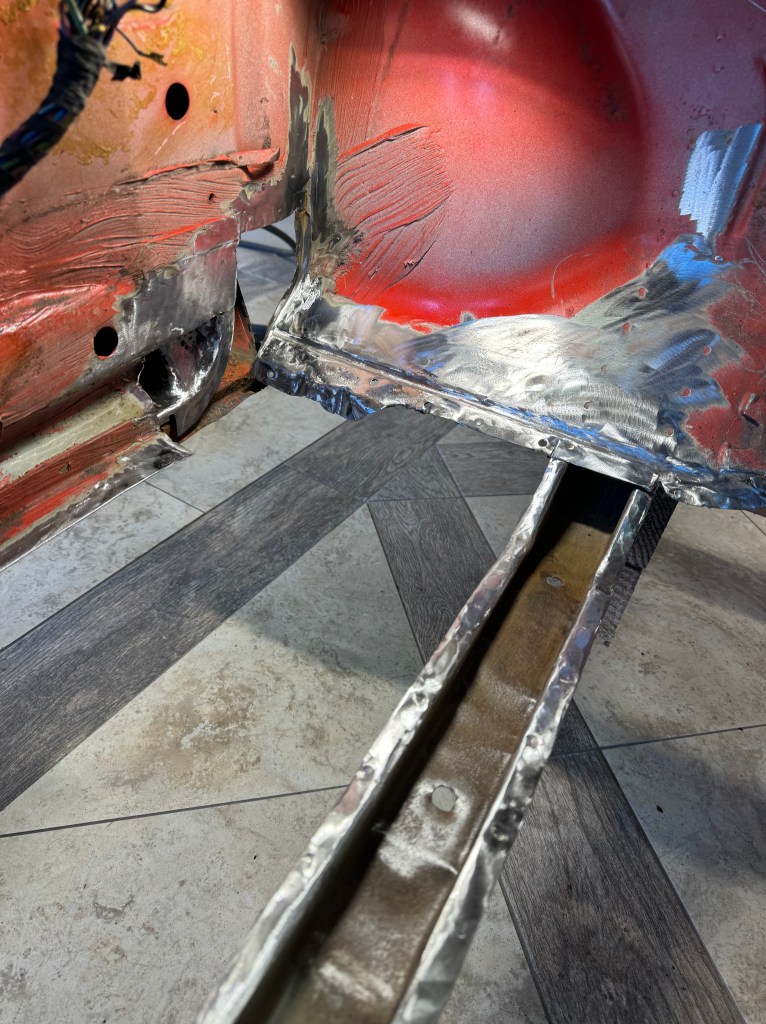

I started with the worst section, a massive hole behind the pedal box that had grown to encompass nearly the entirety of the floor pan. Using a cutoff wheel, I carefully removed not just the obviously rotten metal but also the surrounding areas that looked suspect. We decided to cut around the frame rail as we could always cut it off later if we needed. This was a salvage project, not an all-out restoration.

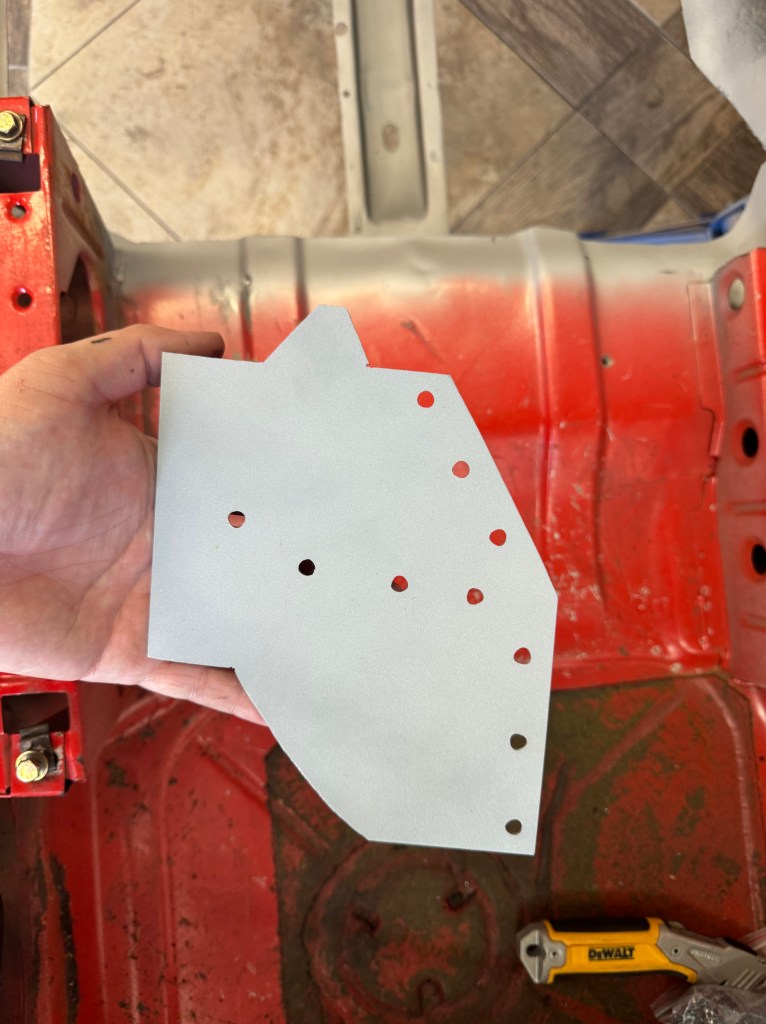

Once I’d removed all the bad metal, the real challenge began: fabricating patch panels. This is where I learned that welding is only part of the equation. I was able to source a brand new floor pan from Wallothnesch, but I wasn’t so lucky with the inner sill panels. I was going to have to make one. The ability to visualize a three-dimensional shape from a flat piece of metal, then cut and form it to fit perfectly, is an art form in itself. I spent hours with cardboard templates, transferring patterns to steel and then carefully cutting and shaping each piece. After drilling some spot weld holes in the panel, it was all ready to go together.

The actual welding process was nerve-wracking at first. This wasn’t practice metal, this was my car, and every bead had to count. I started with tack welds, just small spots to hold everything in place while I checked fit and alignment. In order to prevent heat buildup that could warp the metal, I had to work in sections, welding a bit, then moving to another area.

Gradually, the floor started to take shape again. Each completed section felt like a small victory. The new metal was clean and strong, a stark contrast to the pitted, rusty mess I’d cut out. By the time I finished the last weld, I had a floor that was arguably stronger than what BMW had originally installed. It was a huge victory for me. It didn’t look great, but it had strong welds, no rust, and I did it myself. A proud moment indeed. All that was left was some clean up work. Grinding down the welds, cleaning the panels, and making sure there weren’t any missed spots to let water back in. The car was whole again and once the carpet was back in, you’d never notice there was a fix in place.

Building Something New: Recaro Seat Brackets

With my newfound welding skills and a floor that could actually support them, I decided to upgrade to a pair of Recaro racing seats. The only problem was that Recaro seats don’t bolt directly to BMW floors, they need adapters due to the offset heights of the seat mounts. Rather than buying expensive brackets (most of them sit too high for me), I decided to fabricate my own.

This project was completely different from the floor repair. Instead of fixing something broken, I was creating something entirely new from raw materials. Since I happen to have a set of seat mounts for a pair of Corbeau seats that didn’t work out, all I needed was an adapter to go from Corbeau to Recaro mounting locations. Should be easy right?

I started with flat bar steel, measuring and cutting pieces that would connect the Recaro mounting points to the BMW floor attachment points. The challenge was creating brackets that were not only strong enough to hold me in place during spirited driving but also allowed the seats to sit at the proper height and angle. After cutting and welding the pieces together, I used a mill to drill the correct size hole for everything to mount to.

These brackets had to be perfect; a failure here could literally be life-threatening in an accident. I took my time, triple-checking every measurement and testing every joint before final welding.

When I finally bolted the completed brackets to the car and mounted the Recaro seats, the transformation was incredible. The seats sat perfectly, held me securely, and looked like they’d always belonged in the car. More importantly, I’d built them myself, turning raw steel into functional automotive components. Only time I had ever been prouder was after welding the floor. This new skill was getting me much further than just fixing the floor, and I was thrilled. These brackets were something that seemed so out of reach before, but now, It just another day in the garage.

The Art Project That Taught Me Patience

By this point, I was getting confident with the welder, not overly confident, but competent enough. I’d successfully repaired a car and fabricated functional parts, but I still had a lot to learn about finesse and precision. That’s when I decided to give myself a challenge that would give me some good time with the MIG torch. I purchased a geometric deer head kit on Amazon. A collection of pre-cut metal pieces that could be welded together to create a striking piece of wall art that looked like a deer bust.

At first glance, it seemed simple enough. The pieces were already cut to size, and the instructions showed clearly how everything fit together. But this project quickly became my most challenging yet. Unlike automotive work, where a slightly imperfect weld could be hidden or ground smooth, this art piece demanded precision and patience. Not to mention the metal was significantly thinner. I was recommended to use a TIG welder, but I was determined to use MIG, solely to get better.

The deer head consisted of dozens of small triangular and pentagonal pieces that had to be welded together to create the final three-dimensional form. Each joint had to be perfect – not just structurally sound, but visually clean. There was no room for error, no way to hide sloppy work behind underbody coating or interior trim.

I learned more about welding technique working on this project than I had in months of automotive work. The thin metal required different heat settings and a much more delicate touch. I had to resist the urge to rush, taking time to properly clean each joint and ensure perfect fitment before welding. More than once, I had to cut out a section and start over when a weld didn’t meet my standards or if I burned through the metal.

The deer head project taught me that welding isn’t just about joining metal; it’s about patience, precision, and the willingness to start over when something isn’t right. By the time I hung the finished piece in my garage, I’d developed a level of control and confidence that transformed how I approached every subsequent project. I still can’t “weld dimes” but I can weld. It’s a skill most people don’t have, and arguably don’t need, but I am glad I learned. Nothing beats the feeling of reward that comes from fixing or building something yourself.

The Ripple Effect

What started as a desperate attempt to save a rusty BMW has become so much more than that. Learning to weld opened up a world of possibilities that I never knew existed. Projects that once seemed impossible suddenly became achievable with the right tools and techniques. The skills I learned fixing my BMW floor have been applied to countless other projects now. I’ve fabricated everything from new floor panels to various brackets. Each project builds on the last, teaching new techniques and pushing the boundaries of what’s possible in a home garage.

But perhaps the most valuable lesson has been about perseverance and problem-solving. When you’re holding a welding torch, looking at a pile of raw metal, and envisioning the finished product, you’re not just joining pieces of steel; you’re turning ideas into reality. That’s a skill that extends far beyond the garage.

My 1981 BMW 3-series is almost back on the road, now with a solid floor, custom seat brackets, and the knowledge that it was truly built by my own hands. Every time I sit in it, I’m reminded that sometimes the best solution to a problem isn’t to buy your way out of it, but to learn something new and tackle it yourself. The rust holes that once threatened to end my car’s life became the beginning of a journey that changed how I approach every project, automotive or otherwise.

The welder still sits in my garage, ready for the next challenge. And trust me, there’s always a next challenge when you’re a car enthusiast with the tools and skills to tackle it yourself. Who knows? Maybe I’ll make a roll cage or some suspension bracing, the possibilities are endless.

Leave a Reply